Albania

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the modern state. For other uses, see Albania (disambiguation).

| Republic of Albania

Republika e Shqipërisë (Albanian)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

Motto: (official)

|

||||||

Anthem:

|

||||||

| Capital and largest city |

Tirana 41°20′N 19°48′E |

|||||

| Official languages | Albaniana | |||||

| Demonym | Albanian | |||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic | |||||

| - | President | Bujar Nishani | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Edi Rama | ||||

| - | Chairman of the Parliament | Ilir Meta | ||||

| Legislature | Kuvendi | |||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | Principality of Arbër | 1190 | ||||

| - | Anjou Kingdom of Albania | February 1272 | ||||

| - | Princedom of Albania | 1368 | ||||

| - | League of Lezhë | 2 March 1444 | ||||

| - | Independent Albania | 28 November 1912 | ||||

| - | Principality of Albania (recognized) | 29 July 1913 | ||||

| - | Albanian Republic (the 1st republic) | 31 January 1925 | ||||

| - | Albanian Kingdom | 1 September 1928 | ||||

| - | Albania (under Italy & Nazi Germany) | 7 April 1939 29 November 1944 |

||||

| - | People's Republic of Albania (the 2nd republic) | 11 January 1946 | ||||

| - | People's Socialist Republic of Albania (the 3rd republic) | 28 December 1976 | ||||

| - | Republic of Albania (the 4th republic)/Current constitution | 29 April 1991 28 November 1998 |

||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 28,748 km2 (143rd) 11,100 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 4.7 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2014 estimate | 3,020,209[1] | ||||

| - | 2011 census | 2,821,977[2] | ||||

| - | Density | 98/km2 (63rd) 254/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $32.259 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $11,700[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $14.520 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $5,261[3] | ||||

| Gini (2008) | 26.7[4] low |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | high · 95th |

|||||

| Currency | Lek (ALL) | |||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | 355 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | AL | |||||

| Internet TLD | .al | |||||

| a. | Aromanian, Greek, Macedonian, and other regional languages are government-recognized minority languages. | |||||

Albania is a member of the United Nations, NATO, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Council of Europe and the World Trade Organization. It is one of the founding members of the Energy Community and the Union for the Mediterranean. It is also an official candidate for membership in the European Union.[7]

The modern-day territory of Albania was at various points in history part of the Roman provinces of Dalmatia (southern Illyricum), Macedonia (particularly Epirus Nova), and Moesia Superior. The modern Republic became independent after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in Europe following the Balkan Wars.[8] Albania declared independence in 1912 and was recognized the following year. It then became a Principality, Republic, and Kingdom until being invaded by Italy in 1939, which formed Greater Albania. The latter eventually turned into a Nazi German protectorate in 1943.[9] The following year, a socialist People's Republic was established under the leadership of Enver Hoxha and the Party of Labour. Albania experienced widespread social and political transformations during the communist dictatorship, as well as isolationism from much of the international community. In 1991, the Socialist Republic was dissolved and the Republic of Albania was established.

Albania is a parliamentary republic. As of 2011, the capital, Tirana, was home to 421,286 of the country's 3,020,209[1] people within the city limits, 763,634 in the metropolitan area.[10] Tirana is also the financial capital of the country. Free-market reforms have opened the country to foreign investment, especially in the development of energy and transportation infrastructure.[11][12][13] Albania has a high HDI[5] and provides a universal health care system and free primary and secondary education. Albania is an upper-middle income economy (WB, IMF)[14] with the service sector dominating the country's economy, followed by the industrial sector and agriculture.

Contents

- 1 Etymology

- 2 History

- 3 Albanian state flag

- 4 Government

- 5 Geography

- 6 Economy

- 7 Crime and law enforcement

- 8 Science and technology

- 9 Transport

- 10 Demographics

- 11 Culture

- 12 Education

- 13 Sport

- 14 Entertainment

- 15 Health

- 16 Cuisine

- 17 See also

- 18 Notes

- 19 References

- 20 Further reading

- 21 External links

Etymology

Albania is the Medieval Latin name of the country, which is called Shqipëri by its people, from Medieval Greek Ἀλβανία Albania, besides variants Albanitia or Arbanitia.The name may be derived from the Illyrian tribe of the Albani recorded by Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria who drafted a map in 150 AD[15] that shows the city of Albanopolis[16] (located northeast of Durrës).

The name may have a continuation in the name of a medieval settlement called Albanon and Arbanon, although it is not certain this was the same place.[17] In his History written in 1079–1080, the Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates was the first to refer to Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the Duke of Dyrrachium.[18] During the Middle Ages, the Albanians called their country Arbëri or Arbëni and referred to themselves as Arbëresh or Arbënesh.[19][20]

As early as the 17th century the placename Shqipëria and the ethnic demonym Shqiptarë gradually replaced Arbëria and Arbëresh. The two terms are popularly interpreted as "Land of the Eagles" and "Children of the Eagles".[21][22]

History

Main article: History of Albania

Prehistory

The history of Albania emerged from the prehistoric stage from the 4th century BC, with early records of Illyria in Greco-Roman historiography. The modern territory of Albania has no counterpart in antiquity, comprising parts of the Roman provinces of Dalmatia (southern Illyricum) and Macedonia (particularly Epirus Nova).Middle Ages

The territory now known as Albania remained under Roman (Byzantine) control until the Slavs began to overrun it from 548 and onward,[23] and was captured by Bulgarian Empire in the 9th century. After the weakening of the Byzantine Empire and the Bulgarian Empire in the middle and late 13th century, some of the territory of modern-day Albania was captured by the Serbian Principality. In general, the invaders destroyed or weakened Roman and Byzantine cultural centers in the lands that would become Albania.[24]The territorial nucleus of the Albanian state formed in the Middle Ages, as the Principality of Arbër and the Kingdom of Albania. The Principality of Arbër or Albanon (Albanian): Arbër or Arbëria, was the first Albanian state during the Middle Ages , it was established by archon Progon in the region of Kruja, in ca 1190. Progon, the founder, was succeeded by his sons Gjin and Demetrius, the latter which attained the height of the realm. After the death of Dhimiter, the last of the Progon family, the principality came under Gregory Kamonas, and later Golem. The Principality was dissolved in 1255.[25][26][27] Pipa and Repishti conclude that Arbanon was the first sketch of an "Albanian state", and that it retained semi-autonomous status as the western extremity of an empire (under the Doukai of Epirus or the Laskarids of Nicaea).[28]

Ottoman Albania

Main article: Ottoman Albania

Köprülü Mehmed Pasha was the most effective and influential Ottoman Grand Vizier of Albanian origin.[33]

In the 15th century, when the Ottomans were gaining a firm foothold in the region, Albanian towns were organised into four principal sanjaks. The government fostered trade by settling a sizeable Jewish colony of refugees fleeing persecution in Spain (at the end of the 15th century). Vlorë saw passing through its ports imported merchandise from Europe such as velvets, cotton goods, mohairs, carpets, spices and leather from Bursa and Constantinople. Some citizens of Vlorë even had business associates in Europe.[34]

Albanians could also be found throughout the empire in Iraq, Egypt, Algeria and across the Maghreb, as vital military and administrative retainers.[35] This was partly due to the Devşirme system. The process of Islamization was an incremental one, commencing from the arrival of the Ottomans in the 14th century (to this day, a minority of Albanians are Catholic or Orthodox Christians, though the vast majority became Muslim). Timar holders, the bedrock of early Ottoman control in Southeast Europe, were not necessarily converts to Islam, and occasionally rebelled; the most famous of these rebels is Skanderbeg (his figure would rise up later on, in the 19th century, as a central component of the Albanian national identity). The most significant impact on the Albanians was the gradual Islamisation process of a large majority of the population, although it became widespread only in the 17th century.[36]

Mainly Catholics converted in the 17th century, while the Orthodox Albanians followed suit mainly in the following century. Initially confined to the main city centres of Elbasan and Shkoder, by this period the countryside was also embracing the new religion.[36] The motives for conversion according to some scholars were diverse, depending on the context. The lack of source material does not help when investigating such issues.[37]

Albania remained under Ottoman control as part of the Rumelia province until 1912, when independent Albania was declared.

Era of nationalism and League of Prizren

The League of Prizren was formed on 1 June 1878, in Prizren, Kosovo Vilayet of Ottoman Empire. At first the Ottoman authorities supported the League of Prizren, whose initial position was based on the religious solidarity of Muslim landlords and people connected with the Ottoman administration. The Ottomans favoured and protected Muslim solidarity, and called for defense of Muslim lands, including present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. This was the reason for naming the league The Committee of the Real Muslims (Albanian: Komiteti i Myslimanëve të Vërtetë).[38] The League issued a decree known as Kararname. Its text contained a proclamation that the people from "northern Albania, Epirus and Bosnia" are willing to defend the "territorial integrity" of the Ottoman Empire "by all possible means" from the troops of the Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro. It was signed by 47 Muslim deputies of the League on 18 June 1878.[39] Around 300 Muslims participated in the assembly, including delegates from Bosnia and mutasarrif (sanjakbey) of the Sanjak of Prizren as representatives of the central authorities, and no delegates from Scutari Vilayet.[40]The Ottomans cancelled their support when the League, under the influence of Abdyl bey Frashëri, became focused on working toward Albanian autonomy and requested merging of four Ottoman vilayets (Kosovo, Scutari, Monastir and Ioannina) into a new vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (the Albanian Vilayet). The League used military force to prevent the annexing areas of Plav and Gusinje assigned to Montenegro by the Congress of Berlin. After several battles with Montenegrin troops, the league was defeated by the Ottoman army sent by the Sultan.[41] The Albanian uprising of 1912, the Ottoman defeat in the Balkan Wars and the advance of Montenegrin, Serbian and Greek forces into territories claimed as Albanian, led to the proclamation of independence by Ismail Qemali in Vlora, on 28 November 1912.

Independence

Ismail Qemali and his cabinet during the celebration of the first anniversary of independence in Vlorë on 28 November 1913.

Main article: Albania during World War I

At All-Albanian Congress in Vlorë on 28 November 1912[42] Congress participants constituted the Assembly of Vlorë.[43] The assembly of eighty-three leaders meeting in Vlorë

in November 1912 declared Albania an independent country and set up a

provisional government. The complete text of the declaration[44] was:In Vlora, on the 15th/28th of November. The President of Albania was Ismail Kemal Bey, who spoke of the great perils facing Albania today, the delegates have all decided unanimously that Albania, as of today, should be on her own, free and independent.The Provisional Government of Albania was established on the second session of the assembly held on 4 December 1912. It was a government of ten members, led by Ismail Qemali until his resignation on 22 January 1914.[45] The Assembly also established the Senate (Albanian: Pleqësi) with an advisory role to the government, consisting of 18 members of the Assembly.[46]

Albania's independence was recognized by the Conference of London on 29 July 1913, but the drawing of the borders of the newly established Principality of Albania ignored the demographic realities of the time. The International Commission of Control was established on 15 October 1913 to take care of the administration of newly established Albania until its own political institutions were in order.[47] Its headquarters were in Vlorë.[48] The International Gendarmerie was established as the first law enforcement agency of the Principality of Albania. At the beginning of November the first gendarmerie members arrived in Albania. Wilhelm of Wied was selected as the first prince.[49]

In November 1913 the Albanian pro-Ottoman forces had offered the throne of Albania to the Ottoman war minister of Albanian origin, Izzet Pasha.[50] The pro-Ottoman peasants believed that the new regime of the Principality of Albania was a tool of the six Christian Great Powers and local landowners that owned half of the arable land.[51]

The revolt of Albanian peasants against the new Albanian regime erupted under the leadership of the group of Muslim clerics gathered around Essad Pasha Toptani, who proclaimed himself the savior of Albania and Islam.[52][53] In order to gain support of the Mirdita Catholic volunteers from the northern mountains, Prince of Wied appointed their leader, Prênk Bibë Doda, to be the foreign minister of the Principality of Albania. In May and June 1914 the International Gendarmerie joined by Isa Boletini and his men, mostly from Kosovo,[54] and northern Mirdita Catholics were defeated by the rebels who captured most of Central Albania by the end of August 1914.[55] The regime of Prince of Wied collapsed and he left the country on 3 September 1914.[56]

The short-lived monarchy (1914–1925) was succeeded by an even shorter-lived first Albanian Republic (1925–1928), to be replaced by another monarchy (1928–1939). The kingdom was supported by the fascist regime in Italy and the two countries maintained close relations until Italy's sudden invasion of the country in 1939. Albania was occupied by Fascist Italy and then by Nazi Germany during World War II.

World War II

Main articles: Albanian Kingdom (1939–43) and Albanian resistance during World War II

After being militarily occupied by Italy, from 1939 until 1943 the Albanian Kingdom was a protectorate and a dependency of Italy governed by the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III and his government. After the Axis' invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, territories of Yugoslavia with substantial Albanian population were annexed to Albania: most of Kosovo,[a] as well as Western Macedonia, the town of Tutin in Central Serbia and a strip of Eastern Montenegro.[57]

After the capitulation of Italy in 1943, Nazi Germany occupied Albania

too. The nationalist Balli Kombetar, which had fought against Italy,

formed a "neutral" government in Tirana, and side by side with the

Germans fought against the communist-led National Liberation Movement of

Albania.[58]Communist Albania

Main article: People's Socialist Republic of Albania

By the end of World War II,

the main military and political force in the country, the communist

party, sent forces to northern Albania against the nationalists to

eliminate its rivals. They faced open resistance in Nikaj-Mertur,

Dukagjin and Kelmend (Kelmendi was led by Prek Cali).[59]

On January 15, 1945, a clash took place between partisans of the first

Brigade and nationalist forces at the Tamara Bridge, resulting in the

defeat of the nationalist forces . About 150 Kelmendi[60]

people were killed or tortured. This event was the starting point of

many other athrocities which took place during Enver Hoxha's

dictatorship. Class struggle was strictly applied, human freedom and

human rights were denied. Kelmend region was isolated both by the border

and by lack of roads for another 20 years, the institution of

agricultural cooperative brought about economic backwardness. Many

Kelmendi people fled, some were executed trying to cross the border.After the liberation of Albania from Nazi occupation, the country became a Communist state, the People's Republic of Albania (renamed "the People's Socialist Republic of Albania" in 1976), which was led by Enver Hoxha and the Labour Party of Albania.

The socialist reconstruction of Albania was launched immediately after the annulling of the monarchy and the establishment of a "People's Republic". In 1947, Albania's first railway line was completed, with the second completed eight months later. New land reform laws were passed granting the land to the workers and peasants who tilled it. Agriculture became cooperative, and production increased significantly, leading to Albania's becoming agriculturally self-sufficient. By 1955, illiteracy was eliminated among Albania's adult population.[61]

The Palace of Culture of Tirana, Albania whose first stone was symbolically laid by Nikita Khrushchev

Religious freedoms were severely curtailed during the Communist period, with all forms of worship being outlawed. In August 1945, the Agrarian Reform Law meant that large swaths of property owned by religious groups (mostly Islamic waqfs) were nationalized, along with the estates of monasteries and dioceses. Many believers, with the ulema, and many priests were arrested, tortured and executed. In 1949, a new Decree on Religious Communities required that all their activities be sanctioned by the state alone.[64]

In 1967 Hoxha proclaimed Albania the 'world's first atheist state'. Hundreds of mosques and dozens of Islamic libraries — containing priceless manuscripts — were destroyed.[65] Churches were not spared either, and many were converted into cultural centers for young people. The new law banned all "fascist, religious, warmongerish, antisocialist activity and propaganda." Preaching religion carried a three to ten years prison sentence. Nonetheless, many Albanians continued to practice their belief secretly.

Hoxha's political successor Ramiz Alia oversaw the dismemberment of the "Hoxhaist" state during the breakup of the Eastern Bloc in the later 1980s.

Post-Communist Albania

After protests beginning in 1989 and reforms made by the communist government in 1990, the People's Republic was dissolved in 1991-92 and the Republic of Albania was founded. The Communists retained a stronghold in parliament after popular support in the elections of 1991. However, in March 1992, amid liberalization policies resulting in economic collapse and social unrest, a new front led by the new Democratic Party took power. In the following years, much of the accumulated wealth of the country was invested in a number of Ponzi pyramid banking schemes, which were widely supported by government officials. The schemes swept up somewhere between one-sixth to one-third of the country's population.[66][67] Despite IMF warnings in late 1996, then president Sali Berisha defended the schemes as large investment firms, leading more people to redirect their remittances and sell their homes and cattle for cash to deposit in the schemes.[68] The schemes began to collapse in late 1996, leading many of the investors into initially peaceful protests again the government, requesting their money back. The protests turned violent in February as government forces responded with fire, and in March the police and Republican Guard deserted, leaving their armories open: they were promptly emptied by a number of militias and criminal gangs. The resulting anarchy caused a wave of evacuations of foreign nationals,[69][70] and of refugees.[71] The crisis led Prime Minister Aleksandër Meksi to resign on 11 March 1997, followed by President Sali Berisha in July in the wake of the June General Election. In April 1997, Operation Alba, a UN peacekeeping force led by Italy, entered the country with two goals: Assistance in evacuation of expatriates, and to secure the ground for International Organizations. This was primarily WEU MAPE, who worked with the Government in restructuring the judicial system and police. The Socialist Party won the elections in 1997, and a degree of political stabilization followed. In 1999, the country was affected by the Kosovo War, when a great number of Albanians from Kosovo found refuge in Albania.Post-reconstruction Albania

Albania became a full member of NATO in 2009, and has applied to join the European Union. In 2013, the Socialist Party won the national elections. In June 2014, the Republic of Albania became an official candidate for accession to the European Union.Albanian state flag

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (December 2013) |

| 1912 |  |

Albanian Declaration of Independence | Declaration of independence of the Albanian Vilayet from the Ottoman Empire. Proclaimed in Vlorë on 28 November 1912. |

| 1912–14 |  |

Independent Albania | Parliamentary state and assembly established in Vlorë on 28 November 1912. The government and senate were established on 4 December 1912. Leader Ismail Qemali. |

| 1914–25 |  |

Principality of Albania | Short-lived monarchy headed by William, Prince of Albania, until the abolition of the monarchy in 1925. |

| 1925–28 |  |

Albanian Republic | Official name as enshrined in the Constitution of 1925. A protectorate of the Kingdom of Italy after the Treaties of Tirana of 1926 and 1927. |

| 1928–39 |  |

Kingdom of Albania | Constitutional monarchal rule between 1928 and 1939. A de facto protectorate of the Kingdom of Italy. |

| 1939–43 |  |

Albanian Kingdom under Italy | A protectorate of the Kingdom of Italy. Led by Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III. Ruled by Italian governors after military occupation by Italy from 1939–43. Ceased to exist as an independent country. Part of the Italian Empire. |

| 1943–44 | Albanian Kingdom under Germany | A de jure independent country, between 1943 and 1944. Germans took control after the Armistice with Italy on 8 September 1943. |

|

| 1944–92 |  |

People's Socialist Republic of Albania | From 1944 to 1946 it was known as the Democratic Government of Albania. From 1946 to 1976 it was known as the People's Republic of Albania. |

| since 1992 |  |

Republic of Albania | In 1991 the Socialist Party of Albania took control through democratic elections. In 1992 the Democratic Party of Albania won the new elections. |

-

George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, national hero

(1405–1468) -

Ismail Qemali, hero of Albanian independence (1912–1914)

-

William of Albania, Prince (King) of Albania (7 March 1914 – 3 September 1914)

-

Fan Stilian Noli, Founder of the Albanian Orthodox Church and Prime Minister of Albania (16 June 1924 – 23 December 1924)

-

-

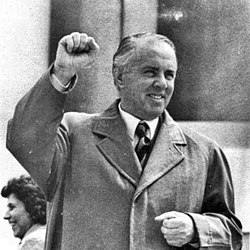

First Secretary Enver Hoxha

(1944–1985)

Government

Main articles: Politics of Albania and Law of Albania

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Albania |

The Euro-Atlantic integration of Albania has been the ultimate goal of the post-communist governments. Albania's EU membership bid has been set as a priority by the European Commission.

Albania, along with Croatia, joined NATO on 1 April 2009, becoming the 27th and 28th members of the alliance.[73]

Executive branch

The head of state in Albania is the President of the Republic. The President is elected to a 5-year term by the Assembly of the Republic of Albania by secret ballot, requiring a 50%+1 majority of the votes of all deputies. The current President of the Republic is Bujar Nishani elected in July 2012.The President has the power to guarantee observation of the constitution and all laws, act as commander in chief of the armed forces, exercise the duties of the Assembly of the Republic of Albania when the Assembly is not in session, and appoint the Chairman of the Council of Ministers (prime minister).

Executive power rests with the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The Chairman of the Council (prime minister) is appointed by the president; ministers are nominated by the president on the basis of the prime minister's recommendation. The People's Assembly must give final approval of the composition of the Council. The Council is responsible for carrying out both foreign and domestic policies. It directs and controls the activities of the ministries and other state organs.

| President | Bujar Nishani | PD | 24 July 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Minister | Edi Rama | PS | 15 September 2013 |

Legislative branch

The Assembly of the Republic of Albania (Kuvendi i Republikës së Shqipërisë) is the lawmaking body in Albania. There are 140 deputies in the Assembly, which are elected through a party-list proportional representation system. The President of the Assembly (or Speaker), who has two deputies, chairs the Assembly. There are 15 permanent commissions, or committees. Parliamentary elections are held at least every four years.The Assembly has the power to decide the direction of domestic and foreign policy; approve or amend the constitution; declare war on another state; ratify or annul international treaties; elect the President of the Republic, the Supreme Court, and the Attorney General and his or her deputies; and control the activity of state radio and television, state news agency and other official information media.

Armed forces

Main article: Military of Albania

Today it consists of: the General Staff, the Albanian Land Force, the Albanian Air Force and the Albanian Naval Force. Increasing the military budget was one of the most important conditions for NATO integration. Military spending has generally been lower than 1.5% since 1996 only to peak in 2009 at 2% and fall again to 1.5%.[76] Since February 2008, Albania has participated officially in NATO's Operation Active Endeavor in the Mediterranean Sea.[77] It was invited to join NATO on 3 April 2008,[78] and it became a full member on 2 April 2009.

Administrative divisions

Main article: Administrative divisions of Albania

| Administrative Divisions of Albania |

|---|

|

|

A new administrative division reform will take effect in June 2015 whereby Municipalities will be reduced to 61 in total. As part of the reform, major town centers in Albania are being physically redesigned and facades painted to reflect a more Mediterranean look.[81][82]

| Counties | Districts | Municipalities | Communes | Localities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Berat | Berat Kuçovë Skrapar |

2 1 2 |

10 2 8 |

122 18 105 |

| 2 | Dibër | Bulqizë Dibër Mat |

1 1 2 |

7 14 10 |

63 141 76 |

| 3 | Durrës | Durrës Krujë |

4 2 |

6 4 |

62 44 |

| 4 | Elbasan | Elbasan Gramsh Librazhd Peqin |

3 1 2 1 |

20 9 9 5 |

177 95 75 49 |

| 5 | Fier | Fier Lushnjë Mallakastër |

3 2 1 |

14 14 8 |

117 121 40 |

| 6 | Gjirokastër | Gjirokastër Përmet Tepelenë |

2 2 2 |

11 7 8 |

96 98 77 |

| 7 | Korçë | Devoll Kolonjë Korçë Pogradec |

1 2 2 1 |

4 6 14 7 |

44 76 153 72 |

| 8 | Kukës | Has Kukës Tropojë |

1 1 1 |

3 14 7 |

30 89 68 |

| 9 | Lezhë | Kurbin Lezhë Mirditë |

3 1 2 |

4 9 5 |

26 62 80 |

| 10 | Shkodër | Malësi e Madhe Pukë Shkodër |

1 2 2 |

5 8 15 |

56 75 141 |

| 11 | Tirana | Kavajë Tirana |

2 3 |

8 16 |

65 154 |

| 12 | Vlorë | Delvinë Sarandë Vlorë |

1 2 4 |

3 7 9 |

38 62 99 |

Geography

Main article: Geography of Albania

Albania has a total area of 28,748 square kilometres (11,100 square miles). It lies between latitudes 39° and 43° N, and mostly between longitudes 19° and 21° E (a small area lies east of 21°). Albania's coastline length is 476 km (296 mi)[83]:240 and extends along the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. The lowlands of the west face the Adriatic Sea.The 70% of the country that is mountainous is rugged and often inaccessible from the outside. The highest mountain is Korab situated in the district of Dibër, reaching up to 2,764 metres (9,068 ft). The climate on the coast is typically Mediterranean with mild, wet winters and warm, sunny, and rather dry summers.

Inland conditions vary depending on elevation, but the higher areas above 1,500 m/5,000 ft are rather cold and frequently snowy in winter; here cold conditions with snow may linger into spring. Besides the capital city of Tirana, which has 420,000 inhabitants, the principal cities are Durrës, Korçë, Elbasan, Shkodër, Gjirokastër, Vlorë and Kukës. In Albanian grammar, a word can have indefinite and definite forms, and this also applies to city names: both Tiranë and Tirana, Shkodër and Shkodra are used.

The three largest and deepest tectonic lakes of the Balkan Peninsula are partly located in Albania. Lake Shkodër in the country's northwest has a surface which can vary between 370 km2 (140 sq mi) and 530 km2, out of which one third belongs to Albania and rest to Montenegro. The Albanian shoreline of the lake is 57 km (35 mi). Ohrid Lake is situated in the country's southeast and is shared between Albania and Republic of Macedonia. It has a maximal depth of 289 meters and a variety of unique flora and fauna can be found there, including "living fossils" and many endemic species. Because of its natural and historical value, Ohrid Lake is under the protection of UNESCO. There is also Butrinti Lake which is a small tectonic lake. It is located in the national park of Butrint.

Climate

The lowlands have mild winters, averaging about 7 °C (45 °F). Summer temperatures average 24 °C (75 °F). In the southern lowlands, temperatures average about 5 °C (9 °F) higher throughout the year. The difference is greater than 5 °C (9 °F) during the summer and somewhat less during the winter.

Inland temperatures are affected more by differences in elevation than by latitude or any other factor. Low winter temperatures in the mountains are caused by the continental air mass that dominates the weather in Eastern Europe and the Balkans. Northerly and northeasterly winds blow much of the time. Average summer temperatures are lower than in the coastal areas and much lower at higher elevations, but daily fluctuations are greater. Daytime maximum temperatures in the interior basins and river valleys are very high, but the nights are almost always cool.

Average precipitation is heavy, a result of the convergence of the prevailing airflow from the Mediterranean Sea and the continental air mass. Because they usually meet at the point where the terrain rises, the heaviest rain falls in the central uplands. Vertical currents initiated when the Mediterranean air is uplifted also cause frequent thunderstorms. Many of these storms are accompanied by high local winds and torrential downpours.

When the continental air mass is weak, Mediterranean winds drop their moisture farther inland. When there is a dominant continental air mass, cold air spills onto the lowland areas, which occurs most frequently in the winter. Because the season's lower temperatures damage olive trees and citrus fruits, groves and orchards are restricted to sheltered places with southern and western exposures, even in areas with high average winter temperatures.

Lowland rainfall averages from 1,000 millimeters (39.4 in) to more than 1,500 millimeters (59.1 in) annually, with the higher levels in the north. Nearly 95% of the rain falls in the winter.

Rainfall in the upland mountain ranges is heavier. Adequate records are not available, and estimates vary widely, but annual averages are probably about 1,800 millimeters (70.9 in) and are as high as 2,550 millimeters (100.4 in) in some northern areas. The western Albanian Alps (valley of Boga) are among the wettest areas in Europe, receiving some 3,100 mm (122.0 in) of rain annually.[84] The seasonal variation is not quite as great in the coastal area.

The higher inland mountains receive less precipitation than the intermediate uplands. Terrain differences cause wide local variations, but the seasonal distribution is the most consistent of any area.

In 2009, an expedition from University of Colorado discovered four small glaciers in the "Cursed" mountains in North Albania. The glaciers are at the relatively low level of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft), almost unique for such a southerly latitude.[85]

Flora and fauna

Although a small country, Albania is distinguished for its rich biological diversity. The variation of geomorphology, climate and terrain create favorable conditions for a number of endemic and sub-endemic species with 27 endemic and 160 subendemic vascular plants present in the country. The total number of plants is over 3250 species, approximately 30% of the entire flora species found in Europe.Over a third of the territory of Albania – about 10,000 square kilometres (3,861 square miles);– is forested and the country is very rich in flora. About 3,000 different species of plants grow in Albania, many of which are used for medicinal purposes. Phytogeographically, Albania belongs to the Boreal Kingdom, the Mediterranean Region and the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region. Coastal regions and lowlands have typical Mediterranean macchia vegetation, whereas oak forests and vegetation are found on higher elevations. Vast forests of black pine, beech and fir are found on higher mountains and alpine grasslands grow at elevations above 1800 meters.[87]

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature and Digital Map of European Ecological Regions by the European Environment Agency, the territory of Albania can be subdivided into three ecoregions: the Illyrian deciduous forests, Pindus Mountains mixed forests and Dinaric Alpine mixed forests. The forests are home to a wide range of mammals, including wolves, bears, wild boars and chamois. Lynx, wildcats, pine martens and polecats are rare, but survive in some parts of the country.

Some of the most significant bird species found in the country include the golden eagle – known as the national symbol of Albania[88] – vulture species, capercaillie and numerous waterfowl. The Albanian forests still maintain significant communities of large mammals such as the brown bear, gray wolf, chamois and wild boar.[87] The north and eastern mountains of the country are home to the last remaining Balkan Lynx – a critically endangered population of the Eurasian lynx.[89]

Economy

Main article: Economy of Albania

See also: Agriculture in Albania

Albania and Croatia have discussed the possibility of jointly building a nuclear power plant at Lake Shkoder, close to the border with Montenegro, a plan that has gathered criticism from Montenegro due to seismicity in the area.[96] In addition, there is some doubt whether Albania would be able to finance a project of such a scale with a total national budget of less than $5 billion.[8] However, in February 2009 Italian company Enel announced plans to build an 800 MW coal-fired power plant in Albania, to diversify electricity sources.[97] Nearly 100% of the electricity is generated by ageing hydroelectric power plants, which are becoming more ineffective due to increasing droughts.[97] However, there have been many private investments in building new hydroelectric power plants such as Devoll Hydro Power Plant and the Ashta hydropower plant.

The country has large deposits of petroleum and natural gas, and produced 26,000 barrels of oil per day in the first quarter of 2014 (BNK-TC).[98][99] Natural gas production, estimated at about 30 million m³, is sufficient to meet consumer demands.[8] Other natural resources include coal, bauxite, copper and iron ore.

Agriculture is the most significant sector, employing a significant proportion of the labor force and generating about 21% of GDP. Albania produces significant amounts of wheat, corn, tobacco, figs (13th largest producer in the world)[100] and olives.

"Tourism is gaining a fair share of Albania's GDP with visitors growing every year. As of 2014 exports seem to gain momentum and have increased 300% from 2008, although their contribution to the GDP is still moderate ( the exports per capita ratio currently stands at 1100 $ ) . Although Albania's growth has slowed in 2013 tourism is expanding rapidly and foreign investments are becoming more common as the government continues the modernization of Albania's institutions."[90]

Tourism

Main article: Tourism in Albania

The bulk of the tourist industry is concentrated along the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea coast. The latter has the most beautiful and pristine beaches, and is often called the Albanian Riviera. Albanian seaside has a considerable length of 360 km, including even the lagoon area which you find within. The seaside has a particular character because it is rich in varieties of sandy beaches, capes, coves, covered bays, lagoons, small gravel beaches, sea caves etc. Some parts of this seaside are very clean ecologically, which represent in this prospective unexplored areas, very rare in Mediterranean area.[103]

The increase in foreign visitors is dramatic, Albania had only 500,000 visitors in 2005, while in 2012 had an estimated 4.2 million tourists. An increase of 740% in only 7 years. Several of the country’s main cities are situated along the pristine seashores of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. An important gateway to the Balkan Peninsula, Albania’s ever-growing road network provides juncture to reach its neighbors in north south, east, and west. Albania is within close proximity to all the major European capitals with short two or three hour flights that are available daily. Tourists can see and experience Albania’s ancient past and traditional culture.[104]

Seventy percent of Albania's terrain is mountainous and there are valleys that spread in a beautiful mosaic of forests, pastures, springs framed by high peaks capped by snow until late summer spreads across them.[105]

Albanian Alps, part of the Prokletije or Accursed Mountains range in Northern Albania bearing the highest mountain peak. The most beautiful mountainous regions that can be easily visited by tourists are Dajti, Thethi, Voskopoja, Valbona, Kelmendi, Prespa, Dukat and Shkreli.

National parks and World Heritage Sites

One of the most impressive mountain national parks is the 4,000-hectare (9,900-acre) Tomorr National Park, established south of the Shkumbin river in the Tomorr Range just east of the beautiful museum-city of Berat, and overlooking the city of Polican. Other important mountain national parks are: Theth (Thethi) National Park in the Shale basin around Theth (2630 hectares)[106] Dajti (Daiti) National Park, 3300 hectares of the mountain overlooking the capital, Tirana and Valbona Valley National Park, in the Valbona Gorge from the gorge entrance through to Rrogam and the surrounding mountains.[107]

Although relatively small, Albania is home to a large number of lakes. Three of the largest lakes are Shkodra, Ohrid and Prespa. [108]

There are a number of associations of the tourism industry such as ATA, Unioni, etc.[109][110]

Albania is home to two World Heritage Sites (Berat and Gjirokastër are listed together)

- Butrint, an ancient Greek and Roman city

- Gjirokastër, a well-preserved Ottoman medieval town

- Berat, the 'town of a thousand and one windows'

Crime and law enforcement

Law enforcement in Albania is primarily the responsibility of the Albanian Police. Albania also has a counter-terrorism unit called RENEA. On a list of 75 countries, Albania listed at 17th lowest crime rate ahead of many western nations such as Denmark, the United Kingdom, Sweden and France.[113] However, homicide is still a problem in the country, especially blood feuds in rural areas of the north and domestic crime.[114] In 2014 about 3000 Albanian families were estimated to be involved in blood feuds and this had since the fall of Communism led to the deaths of 10,000 people.[115]Science and technology

Main article: Science and technology in Albania

From 1993 human resources in sciences and technology have drastically

decreased. Various surveys show that during 1991–2005, approximately

50% of the professors and research scientists of the universities and

science institutions in the country have emigrated.[116]However in 2009 the government approved the "National Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation in Albania"[117] covering the period 2009–2015. It aims to triple public spending on research and development (R&D) to 0.6% of GDP and augment the share of gross domestic expenditure on R&D from foreign sources, including via the European Union's Framework Programmes for Research, to the point where it covers 40% of research spending, among others.

Transport

Main article: Transport in Albania

Highways

Currently there are three main motorways in Albania: the dual carriageway connecting Durrës with Vlorë, the Albania–Kosovo Highway, and the Tirana–Elbasan Highway.The A1 Albania–Kosovo Highway links Kosovo to Albania's Adriatic coast: the Albanian side was completed in June 2009,[118] and now it takes only two hours and a half to go from the Kosovo border to Durrës. Overall the highway will be around 250 km (155 mi) when it reaches Prishtina. The project was the biggest and most expensive infrastructure project ever undertaken in Albania. The cost of the highway appears to have breached €800 million, although the exact cost for the total highway has yet to be confirmed by the government.

Two additional highways will be built in Albania in the near future: Corridor VIII, which will link Albania with the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria, and the north-south highway, which corresponds to the Albanian side of the Adriatic–Ionian motorway, a larger regional highway connecting Croatia with Greece along the Adriatic and Ionian coasts. When all three corridors are completed Albania will have an estimated 759 kilometers of highway linking it with all its neighboring countries: Kosovo, the Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, and Greece.

Aviation

The civil air transport in Albania marked its beginnings in November 1924, when the Republic of Albania signed a governmental agreement with German air company Deutsche Luft Hansa. On the basis of a ten-year concession agreement, the Albanian Airlines Company Adria Aero Lloyd was established.[citation needed] In the spring of 1925, the first domestic flights from Tirana to Shkodër and Vlorë began.[citation needed]In August 1927, the office of Civil Aviation of Air Traffic Ministry of Italy purchased Adria Aero Lloyd. The company, now in Italian hands, expanded its flights to other cities, such as Elbasan, Korçë, Kukës, Peshkopi and Gjirokastër, and opened up international lines to Rome, Milan, Thessaloniki, Sofia, Belgrade, and Podgorica.

The construction of a more modern airport in Laprakë started in 1934 and was completed by the end of 1935. This new airport, which was later officially named "Airport of Tirana", was constructed in conformity with optimal technological parameters of that time, with a reinforced concrete runway of 2,700 m (8,858 ft), and complemented with technical equipment and appropriate buildings.

During 1955–1957, the Rinasi Airport was constructed for military purposes. Later, its administration was shifted to the Ministry of Transport. On 25 January 1957 the State-owned Enterprise of International Air Transport (Albtransport) established its headquarters in Tirana. Aeroflot, Jat Airways, Malév, TAROM and Interflug were the air companies that started to have flights with Albania until 1960.[119]

During 1960–1978, several airlines ceased to operate in Albania due to the impact of the politics, resulting in a decrease of influx of flights and passengers. In 1977 Albania's government signed an agreement with Greece to open the country's first air links with non-communist Europe. As a result, Olympic Airways was the first non-communist airline to commercially fly into Albania after World War II. By 1991 Albania had air links with many major European cities, including Paris, Rome, Zürich, Vienna and Budapest, but no regular domestic air service.[119]

A French-Albanian joint venture Ada Air, was launched in Albania as the first private airline, in 1991. The company offered flights in a thirty-six-passenger airplane four days a week between Tirana and Bari, Italy and a charter service for domestic and international destinations.[119]

From 1989 to 1991, because of political changes in the Eastern European countries, Albania adhered to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), opened its air space to international flights, and had its duties of Air Traffic Control defined. As a result of these developments, conditions were created to separate the activities of air traffic control from Albtransport. Instead, the National Agency of Air Traffic (NATA) was established as an independent enterprise. In addition, during these years, governmental agreements of civil air transport were established with countries such as Bulgaria, Germany, Slovenia, Italy, Russia, Austria, the UK and Macedonia.

Railways

Main articles: Rail transport in Albania and Hekurudha Shqiptare

The railways in Albania are administered by the national railway company Hekurudha Shqiptare (HSH) (which means Albanian Railways). It operates a 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) gauge (standard gauge) rail system in Albania. All trains are hauled by Czech-built ČKD diesel-electric locomotives.The railway system was extensively promoted by the totalitarian regime of Enver Hoxha, during which time the use of private transport was effectively prohibited. Since the collapse of the former regime, there has been a considerable increase in car ownership and bus usage. Whilst some of the country's roads are still in very poor condition, there have been other developments (such as the construction of a motorway between Tirana and Durrës) which have taken much traffic away from the railways.[citation needed]

Demographics

Main article: Demographics of Albania

| Population in Albania[120] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1971 | 2.2 | ||

| 1990 | 3.3 | ||

| 2008 | 3.1 | ||

| 2011 | 2.8 | ||

| Source: OECD/World Bank | |||

Issues of ethnicity are a delicate topic and subject to debate. "Although official statistics have suggested that Albania is one of the most homogenous countries in the region (with an over 97 per cent Albanian majority) minority groups (such as Greeks, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Roma and Vlachs/Aromanians) have often questioned the official data, claiming a larger share in the country’s population."[125] The last census that contained ethnographic data (before the 2011 one) was conducted in 1989.[126]

Albania recognizes three national minorities, Greeks, Macedonians and Montenegrins, and two cultural minorities, Aromanians and Romani people.[127] Other Albanian minorities are Bulgarians, Gorani, Serbs, Balkan Egyptians, Bosniaks and Jews. Regarding the Greeks, "it is difficult to know how many Greeks there are in Albania. The Greek government, it is typically claimed, says that there are around 300,000 ethnic Greeks in Albania, but most western estimates are around 200,000 mark (although EEN puts the number at a probable 100,000)."[128][129][130][131][132] The Albanian government puts the number at only 24,243."[133] The CIA World Factbook estimates the Greek minority at 0.9%[134] of the total population and the US State Department uses 1.17% for Greeks and 0.23% for other minorities.[135]

According to the 2011 census the population of Albania declared the following ethnic affiliation: Albanians 2,312,356 (82.6% of the total), Greeks 24,243 (0.9%), Macedonians 5,512 (0.2%), Montenegrins 366 (0.01%), Aromanians 8,266 (0.30%), Romani 8,301 (0.3%), Balkan Egyptians 3,368 (0.1%), other ethnicities 2,644 (0.1%), no declared ethnicity 390,938 (14.0%), and not relevant 44,144 (1.6%).[2]

Macedonian and some Greek minority groups have sharply criticized Article 20 of the Census law, according to which a $1,000 fine will be imposed on anyone who will declare an ethnicity other than what is stated on his or her birth certificate. This is claimed to be an attempt to intimidate minorities into declaring Albanian ethnicity, according to them the Albanian government has stated that it will jail anyone who does not participate in the census or refuse to declare his or her ethnicity.[136] Genc Pollo, the minister in charge has declared that: "Albanian citizens will be able to freely express their ethnic and religious affiliation and mother tongue. However, they are not forced to answer these sensitive questions".[137] The amendments criticized do not include jailing or forced declaration of ethnicity or religion; only a fine is envisioned which can be overthrown by court.[138][139]

Greek representatives form part of the Albanian parliament and the government has invited Albanian Greeks to register, as the only way to improve their status.[125] On the other hand, nationalists, various intellectuals organizations and political parties in Albania have expressed their concern that the census might artificially increase the number of Greek minority, which might be then exploited by Greece to threaten Albania's territorial integrity.[125][125][140][140][141][142][143][144][145]

Language

Main article: Languages of Albania

Albanian is the official language of Albania. Its standard spoken and written form is revised and merged from the two main dialects, Gheg and Tosk, though it is notably based more on the Tosk dialect. Shkumbin river is the rough dividing line between the two dialects. Also a dialect of Greek that preserves features now lost in standard modern Greek is spoken in areas inhabited by the Greek minority. Other languages spoken by ethnic minorities in Albania include Vlach, Serbian, Macedonian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Gorani, and Roma.[146] Macedonian is official in Pustec Municipality in East Albania.According to the 2011 population census, 2,765,610 or 98.767% of the population declared Albanian as their mother tongue ("mother tongue is defined as the first or main language spoken at home during childhood").[2]

Religion

Main article: Religion in Albania

See also: Freedom of religion in Albania

According to 2011 census, 58.79% of Albania adheres to Islam, Christianity

is practiced by 17.06% of the population, making it the 2nd largest

religion in the country and 24.29% of the total population is either irreligious or belongs to other religious groups.[147]

The Albanian Orthodox church refused to recognize the 2011 census

results regarding faith, saying that 24% of the total population are

Albanian Orthodox Christians rather than just 6.75%.[148] Before World War II, 70% of the population were Muslims, 20% Eastern Orthodox, and 10% Roman Catholics.[8]

According to a 2010 survey, religion today plays an important role in

the lives of only 39% of Albanians, and Albania is ranked among the

least religious countries in the world.[149] A 2012 Pew Research Center study found that 65% of Albanian Muslims are non-denominational Muslims.[150]The Albanians first appear in the historical record in Byzantine sources of the late 11th century. At this point, they were already fully Christianized. Islam later emerged as the majority religion during the centuries of Ottoman rule, though a significant Christian minority remained. After independence (1912) from the Ottoman Empire, the Albanian republican, monarchic and later Communist regimes followed a systematic policy of separating religion from official functions and cultural life. Albania never had an official state religion either as a republic or as a kingdom. In the 20th century, the clergy of all faiths was weakened under the monarchy, and ultimately eradicated during the 1940s and 1950s, under the state policy of obliterating all organized religion from Albanian territories.

The Communist regime that took control of Albania after World War II persecuted and suppressed religious observance and institutions and entirely banned religion to the point where Albania was officially declared to be the world's first atheist state. Religious freedom has returned to Albania since the regime's change in 1992. Albania joined the Organisation of the Islamic Conference in 1992, following the fall of the communist government, but will not be attending the 2014 conference due a dispute regarding the fact that its parliament never ratified the country's membership.[151] Albanian Muslim populations (mainly secular and of the Sunni branch) are found throughout the country whereas Albanian Orthodox Christians as well as Bektashis are concentrated in the south and Roman Catholics are found in the north of the country.[152]

The first recorded Albanian Protestant was Said Toptani, who traveled around Europe, and in 1853 returned to Tirana and preached Protestantism. He was arrested and imprisoned by the Ottoman authorities in 1864. Mainline evangelical Protestants date back to the work of Congregational and later Methodist missionaries and the work of the British and Foreign Bible Society in the 19th century. The Evangelical Alliance, which is known as VUSh, was founded in 1892. Today VUSh has about 160 member congregations from different Protestant denominations. VUSh organizes marches in Tirana including one against blood feuds in 2010. Bibles are provided by the Interconfessional Bible Society of Albania. The first full Albanian Bible to be printed was the Filipaj translation printed in 1990.

Seventh-day Adventist Church,[153][154] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,[155] and Jehovah's Witnesses[156] also have a number of adherents in Albania.

Albania was the only country in Europe where Jewish population experienced growth during the Holocaust.[157] After the mass emigration to Israel since the fall of Communist regime, only 200 Albanian Jews are left in the country today.[158][159]

-

Orthodox Cathedral in Durrës, Albania

-

Et'hem Bey Mosque and Tirana Clock Tower

-

World Headquarters of the Bektashi Order in Tirana.

Culture

Main article: Culture of Albania

See also: Tourism in Albania

Music and folklore

Main article: Music of Albania

Albanian folk music falls into three stylistic groups, with other important music areas around Shkodër and Tirana; the major groupings are the Ghegs of the north and southern Labs and Tosks.

The northern and southern traditions are contrasted by the "rugged and

heroic" tone of the north and the "relaxed" form of the south.These disparate styles are unified by "the intensity that both performers and listeners give to their music as a medium for patriotic expression and as a vehicle carrying the narrative of oral history", as well as certain characteristics like the use of rhythms such as 3/8, 5/8 and 10/8.[160] The first compilation of Albanian folk music was made by Pjetër Dungu in 1940.

Albanian folk songs can be divided into major groups, the heroic epics of the north, and the sweetly melodic lullabies, love songs, wedding music, work songs and other kinds of song. The music of various festivals and holidays is also an important part of Albanian folk song, especially those that celebrate St. Lazarus Day, which inaugurates the springtime. Lullabies and vajtims are very important kinds of Albanian folk song, and are generally performed by solo women.[161]

Albanian language and literature

Some scholars believe that Albanian derives from Illyrian[162] while others[163] claim that it derives from Daco-Thracian. (Illyrian and Daco-Thracian, however, might have been closely related languages; see Thraco-Illyrian.)

Establishing longer relations, Albanian is often compared to Balto-Slavic on the one hand and Germanic on the other, both of which share a number of isoglosses with Albanian. Moreover, Albanian has undergone a vowel shift in which stressed, long o has fallen to a, much like in the former and opposite the latter. Likewise, Albanian has taken the old relative jos and innovatively used it exclusively to qualify adjectives, much in the way Balto-Slavic has used this word to provide the definite ending of adjectives.

The cultural renaissance was first of all expressed through the development of the Albanian language in the area of church texts and publications, mainly of the Catholic region in the North, but also of the Orthodox in the South. The Protestant reforms invigorated hopes for the development of the local language and literary tradition when cleric Gjon Buzuku brought into the Albanian language the Catholic liturgy, trying to do for the Albanian language what Luther did for German.

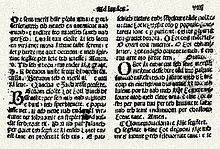

The earliest evidence dates from 1332 AD with a Latin report from the French Dominican Guillelmus Adae, Archbishop of Antivari, who wrote that Albanians used Latin letters in their books although their language was quite different from Latin. Other significant examples include: a baptism formula (Unte paghesont premenit Atit et Birit et spertit senit) from 1462, written in Albanian within a Latin text by the Bishop of Durrës, Pal Engjëlli; a glossary of Albanian words of 1497 by Arnold von Harff, a German who had travelled through Albania, and a 15th-century fragment of the Bible from the Gospel of Matthew, also in Albanian, but written in Greek letters.

The National Museum of Albania features exhibits from Illyrian times to the fall of Communism in the 1990s.

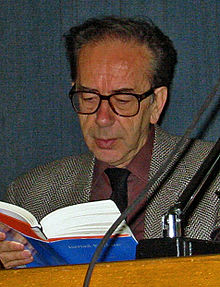

During the 16th to 17th centuries, the catechism E mbësuame krishterë (Christian Teachings) (1592) by Lekë Matrënga, Doktrina e krishterë (The Christian Doctrine) (1618) and Rituale romanum (1621) by Pjetër Budi, the first writer of original Albanian prose and poetry, an apology for George Castriot (1636) by Frang Bardhi, who also published a dictionary and folklore creations, the theological-philosophical treaty Cuneus Prophetarum (The Band of Prophets) (1685) by Pjetër Bogdani, the most universal personality of Albanian Middle Ages, were published in Albanian. The most famous Albanian writer is probably Ismail Kadare.

Education

Main article: Education in Albania

Before the establishment of the People's Republic, Albania's illiteracy rate was as high as 85%. Schools were scarce between World War I and World War II. When the People's Republic was established in 1945, the Party

gave high priority to wiping out illiteracy. As part of a vast social

campaign, anyone between the ages of 12 and 40 who could not read or

write was mandated to attend classes to learn. By 1955, illiteracy was

virtually eliminated among Albania's adult population.[164]Today the overall literacy rate in Albania is 98.7%; the male literacy rate is 99.2% and female literacy rate is 98.3%.[8] With large population movements in the 1990s to urban areas, the provision of education has undergone transformation as well. The University of Tirana is the oldest university in Albania, having been founded in October 1957.

Sport

Football is the most popular sport in Albania, both at a participatory and spectator level. The sport is governed by the Football Association of Albania (Albanian: Federata Shqiptare e Futbollit, F.SH.F.), created in 1930, member of FIFA and a founding member of UEFA. Other sports played include basketball, volleyball, tennis, swimming, rugby union, and gymnastics.Entertainment

Main article: Radio Televizioni Shqiptar

See also: Television in Albania and List of radio stations in Albania

Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSH) is the public radio and TV broadcaster of Albania, founded by King Zog in 1938. RTSH runs three analogue television stations as TVSH Televizioni Shqiptar, four digital thematic stations as RTSH, and three radio stations using the name Radio Tirana.

In addition, 4 regional radio stations serve in the four extremities of

Albania. The international service broadcasts radio programmes in

Albanian and seven other languages via medium wave (AM) and short wave (SW).[165] The international service has used the theme from the song "Keputa një gjethe dafine" as its signature tune. The international television service via satellite was launched since 1993 and aims at Albanian communities in Kosovo, Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro and northern Greece, plus the Albanian diaspora

in the rest of Europe. RTSH has a past of being heavily influenced by

the ruling party in its reporting, whether that party be left or right

wing.According to the Albanian Media Authority, AMA, Albania has an estimated 257 media outlets, including 66 radio stations and 67 television stations, with three national, 62 local and more than 50 cable TV stations. Last years Albania has organized several shows as a part of worldwide series like Dancing with the Stars, Big Brother Albania, Albanians Got Talent, The Voice of Albania, and X Factor Albania.

Health

Health care has been in a steep decline since the collapse of socialism in the country, but a process of modernization has been taking place since 2000.[166] In the 2000s, there were 51 hospitals in the country, including a military hospital and specialist facilities.[166] Albania has successfully eradicated diseases such as malaria.Life expectancy is estimated at 77.59 years, ranking 51st worldwide, and outperforming a number of European Union countries, such as Hungary and the Czech Republic.[167] The most common causes of death are circulatory diseases followed by cancerous illnesses. Demographic and Health Surveys completed a survey in April 2009, detailing various health statistics in Albania, including male circumcision, abortion and more.[168]

The Faculty of Medicine of the University of Tirana is the main medical school in the country. There are also nursing schools in other cities. Newsweek ranked Albania 57 out of 100 Best Countries in the World in 2010.[169]

The general improvement of health conditions in the country is reflected in the lower mortality rate, down to an estimated 6.49 deaths per 1,000 in 2000, as compared with 17.8 per 1,000 in 1938. In 2000, average life expectancy was estimated at 74 years, compared to 38 years at the end of World War II. Albania's infant mortality rate, estimated at 20 per 1,000 live births in 2000, has also declined over the years since the high rate of 151 per 1,000 live births in 1960. There were 69,802 births in 1999 and the fertility rate in 1999 was 2.5 while the maternal mortality rate was 65 per 100,000 live births in 1993. In addition, in 1997, Albania had high immunization rates for children up to one year old: tuberculosis at 94%; diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus, 99%; measles, 95%; and polio, 99.5%. In 1996, the incidence of tuberculosis was 23 in 100,000 people. In 1995 there were two reported cases of AIDS and seven cases in 1996. In 2000 the number of people living with HIV/AIDS was estimated at less than 100. The leading causes of death are cardiovascular disease, trauma, cancer, and respiratory disease.

Alternative medicine is also practiced among the population in the form of herbal remedies as the country is a large exporter of aromatic and medicinal herbs.

Cuisine

Main article: Albanian cuisine

The cuisine of Albania – as with most Mediterranean and Balkan

nations – is strongly influenced by its long history. At different

times, the territory which is now Albania has been claimed or occupied

by Greece, Serbia, Italy and the Ottoman Turks and each group has left its mark on Albanian cuisine. The main meal of Albanians is the midday meal, which is usually accompanied by a salad of fresh vegetables such as tomatoes, cucumbers, green peppers and olives with olive oil, vinegar and salt. It also includes a main dish of vegetables and meat. Seafood specialties are also common in the coastal cities of Durrës, Sarandë and Vlorë. In high elevation localities, smoked meat and pickled preserves are common.History of Albania

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Part of a series on the

|

|---|

| History of Albania |

|

| Albania portal |

The territorial nucleus of the Albanian state was formed in the Middle Ages as the Principality of Arbër and a Sicilian dependency known as the medieval Kingdom of Albania. The area was part of the Serbian Empire, but passed to the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century. It remained under Ottoman control as part of the province of Rumelia until 1912, when the first independent Albanian state was founded by an Albanian Declaration of Independence following a short occupation by the Kingdom of Serbia.[1] The formation of an Albanian national consciousness dates to the later 19th century and is part of the larger phenomenon of the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire.

A short-lived monarchical state known as the Principality of Albania (1914–1925) was succeeded by an even shorter-lived first Albanian Republic (1925–1928). Another monarchy, the Kingdom of Albania (1928–39), replaced the republic. The country endured an occupation by Italy just prior to World War II. After the collapse of the Axis powers, Albania became a communist state, the Socialist People's Republic of Albania, which for most of its duration was dominated by Enver Hoxha (died 1985). Hoxha's political heir Ramiz Alia oversaw the disintegration of the "Hoxhaist" state during the wider collapse of the Eastern Bloc in the later 1980s.

The communist regime collapsed in 1990, and the former communist Party of Labour of Albania was routed in elections in March 1992, amid economic collapse and social unrest. The unstable economic situation led to an Albanian diaspora, mostly to Italy, Greece, Switzerland, Germany and North America during the 1990s. The crisis peaked in the Albanian Turmoil of 1997. An amelioration of the economic and political conditions in the early years of the 21st century enabled Albania to become a full member of NATO in 2009. The country is applying to join the European Union.

Contents

- 1 Prehistory

- 2 Antiquity

- 3 Middle Ages

- 4 Ottoman rule (1431-1912)

- 5 Independence of Albania (1912)

- 6 Principality of Albania

- 7 Albanian Republic (1924–1928)

- 8 Kingdom of Albania (1928–1939)

- 9 Albania during World War II

- 10 Socialist Albania (1944–1992)

- 11 Post-Socialist Albania

- 12 See also

- 13 References

- 14 Bibliography

- 15 External links

Prehistory

Main article: Prehistoric Balkans

The first traces of human presence in Albania, dating to the Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic eras, were found in the village of Xarrë, near Sarandë and Mount Dajt near Tiranë.[2]

The objects found in a cave near Xarrë include flint and jasper objects

and fossilized animal bones, while those found at Mount Dajt comprise

bone and stone tools similar to those of the Aurignacian culture. The Paeolithic finds of Albania show great similarities with objects of the same era found at Crvena Stijena in Montenegro and north-western Greece.[2]Several Bronze Age artifacts from tumulus burials have been unearthed in central and southern Albania that show close connection with sites in southwestern Macedonia and Lefkada, Greece. Archeologists have come to the conclusion that these regions were inhabited from the middle of the third millennium BC by Indo-European people who spoke a Proto-Greek language. A part of this population later moved to Mycenae around 1600 BC and founded the Mycenaean civilisation there.[3][4][5] Another population group, the Illirii, probably the southernmost Illyrian tribe of that time[6] that lived on the border of Albania and Montenegro, possibly neighbored the Greek tribes.[6][7]

In the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age a number of possible population movements occurred in the territories of modern Albania, for example the settlement of the Bryges in areas of southern Albania-northwestern Greece[8] and Illyrian tribes into central Albania.[5] The latter derived from early an Indo-European presence in the western Balkan Peninsula. The movement of the Illyrian tribes can be assumed to coincide with the beginning Iron Age in the Balkans during the early 1st millennium BC.[9]

Archaeologists associate the Illyrians with the Hallstatt culture, an Iron Age people noted for production of iron, bronze swords with winged-shaped handles, and the domestication of horses. It is impossible to delineate Illyrian tribes from Paleo-Balkans in a strict linguistic sense, but areas classically included under "Illyrian" for the Balkans Iron Age include the area of the Danube, Sava, and Morava rivers to the Adriatic Sea and the Shar Mountains.[10]

Antiquity

Illyrians

The Illyrians (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυριοί; Latin: Illyrii or Illyri) were a group of tribes who inhabited the Western Balkans during classical antiquity. The territory the tribes covered came to be known as Illyria to Hellenistic and Roman authors, corresponding roughly to the area between Adriatic sea in west, Drava river in North, Morava river in east and the mouth of Vjosë river in south.[11][12] The first account of Illyrian peoples comes from Periplus or Coastal passage an ancient Greek text of the middle of the 4th century BC.[13]The Illyrian tribes that resided in the region of modern Albania were the Taulantii and Albanoi[14] in central Albania[15] the Parthini, the Abri and the Caviii in the north, the Enchelei in the east,[16] the Bylliones in the south and several others. In the westernmost parts of the territory of Albania along with the Illyrian tribes lived the Bryges,[17] a Phrygian people, and in the south[18][19] lived the Greek tribe of the Chaonians.[17][20][21]

In the 4th century BC, the Illyrian king Bardyllis, (Albanian: Bardhëylli, which means white star) united several Illyrian tribes and engaged in conflict with Macedon to the southeast, but was defeated. Bardyllis was succeeded by Grabos,[22] then by Bardyllis II,[23] and then by Cleitus the Illyrian,[23] who was defeated by Alexander the Great.Queen Teuta[24] of the Ardiaei's forces extended their operations further southward into the Ionian Sea, defeating the combined Achaean and Aetolian fleet in the battle of Paxos and capturing the island of Corcyra, which put them in position to breach the important trade routes between the mainland of Greece and the Greek cities in Italy.[25] Later on, in 229 BC, she clashed with the Romans and initiated the Illyrian Wars, which resulted in defeat and in the end of Illyrian independence by 168 BC, when King Gentius was defeated by a Roman army.

Greeks

Roman Era

Main articles: Macedonia (Roman province), Dalmatia (Roman province), Illyricum (Roman province) and Moesia Superior

The lands comprising modern-day Albania were incorporated into the Roman Empire as part of the province of Illyricum above the river Drin, and Roman Macedonia (specifically as Epirus Nova) below it. The western part of the Via Egnatia ran inside modern Albania, ending at Dyrrachium. Illyricum was later divided into the provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia.The Roman province of Illyricum or[27][28] Illyris Romana or Illyris Barbara or Illyria Barbara replaced most of the region of Illyria. It stretched from the Drilon River in modern Albania to Istria (Croatia) in the west and to the Sava River (Bosnia and Herzegovina) in the north. Salona (near modern Split in Croatia) functioned as its capital. The regions which it included changed through the centuries though a great part of ancient Illyria remained part of Illyricum.

South Illyria became Epirus Nova, part of the Roman province of Macedonia. In 357 AD the region was part of the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum one of four large praetorian prefectures into which the Late Roman Empire was divided. By 395 AD dioceses in which the region was divided were the Diocese of Dacia (as Pravealitana), and the Diocese of Macedonia (as Epirus Nova). Most of the region of modern Albania corresponds to the Epirus Nova.

Christianization

Christianity came to Epirus nova, then part of the Roman province of Macedonia.[29] Since the 1st and 2nd century AD, Christianity had become the established religion in Byzantium, supplanting pagan polytheism and eclipsing for the most part the humanistic world outlook and institutions inherited from the Greek and Roman civilizations. The Durrës Amphitheatre ((Albanian: Amfiteatri i Durrësit) )) is a historic monument from the time period located in Durrës, Albania, that was used to preach Christianity to civilians during that time.When the Roman Empire was divided into eastern and western halves in AD 395, Illyria east of the Drinus River (Drina between Bosnia and Serbia), including the lands that now form Albania, were administered by the Eastern Empire but were ecclesiastically dependent on Rome. Though the country was in the fold of Byzantium, Christians in the region remained under the jurisdiction of the Roman pope until 732. In that year the iconoclast Byzantine emperor Leo III, angered by archbishops of the region because they had supported Rome in the Iconoclastic Controversy, detached the church of the province from the Roman pope and placed it under the patriarch of Constantinople.

When the Christian church split in 1054 between Eastern Orthodoxy and Catholicism, the region of southern Albania retained its ties to Constantinople, while the north reverted to the jurisdiction of Rome. This split marked the first significant religious fragmentation of the country.

After the formation of the Slav principality of Dioclia (modern Montenegro), the metropolitan see of Bar was created in 1089, and dioceses in northern Albania (Shkodër, Ulcinj) became its suffragans. Starting in 1019, Albanian dioceses of the Byzantine rite were suffragans of the independent Archdiocese of Ohrid until Dyrrachion and Nicopolis, were re-established as metropolitan sees. Thereafter, only the dioceses in inner Albania (Elbasan, Krujë) remained attached to Ohrid. In the 13th century during the Venetian occupation, the Latin Archdiocese of Durrës was founded.

Middle Ages

Main article: Albania in the Middle Ages

Byzantine rule and barbarian invasions (395-1347)

Main article: Albania under the Byzantine Empire

After the region fell to the Romans in 168 BC it became part of Epirus nova that was in turn part of the Roman province of Macedonia. Later it was part of provinces of the Byzantine empire called Themes.When the Roman Empire was divided into East and West in 395, the territories of modern Albania became part of the Byzantine Empire. Beginning in the first decades of Byzantine rule (until 461), the region suffered devastating raids by Visigoths, Huns, and Ostrogoths. In the 6th and 7th centuries, the region experienced an influx of Slavs.

The new administrative system of the themes, or military provinces created by the Byzantine Empire, contributed to the eventual rise of feudalism in Albania, as peasant soldiers who served military lords became serfs on their landed estates. Among the leading families of the Albanian feudal nobility were the Balsha, Thopia, Shpata, Muzaka, Dukagjini and Kastrioti. The first three of these rose later to become rulers of principalities during the years 1355-1400. Many Albanians converted to the Roman Catholic Church at that period.

In the first decades under Byzantine rule (until 461), Epirus nova suffered the devastation of raids by Visigoths, Huns, and Ostrogoths. Not long after these barbarian invaders swept through the Balkans, the Slavs appeared. Between the 6th and 8th centuries they settled in Roman territories. In the 4th century, barbarian tribes began to prey upon the Roman Empire. The Germanic Goths and Asiatic Huns were the first to arrive, invading in mid-century; the Avars attacked in AD 570; and the White Croatian tribes invaded in the early 7th century. In general, the invaders destroyed or weakened Roman and Byzantine cultural centers in the lands that would become Albania.[30]

Bulgarian Empire

Main article: Albania under the Bulgarian Empire

The location of Arbanon in the 11th century. According to Ducellier the castle of Petrela was the access point to the region known with this name[31] On the location of Arbanon see also[32]

In the Middle Ages, the name Arberia (see Origin and history of the name Albania) began to be increasingly applied to the region now comprising the nation of Albania. The first undisputed mention of Albanians in the historical record is attested in Byzantine source for the first time in 1079–1080, in a work titled History by Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates, who referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. A later reference to Albanians from the same Attaliates, regarding the participation of Albanians in a rebellion around 1078, is undisputed.[33]