Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (October 2010) |

| Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia | ||||||

| Reino de la Araucanía y la Patagonia | ||||||

| Unrecognized state | ||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Motto Spanish: Independencia y Libertad English: Independence and Liberty |

||||||

|

Location of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia, in Chile and Argentina

|

||||||

| Capital | Perquenco, in current Cautín Province, La Araucanía Region, Chile | |||||

| Capital-in-exile | Paris, France[1] | |||||

| Languages | Mapudungun, French | |||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||

| King | ||||||

| - | 1860–1878 | Orélie-Antoine I (Aurelio Antonio I) | ||||

| Historical era | Occupation of the Araucanía/Conquest of the Desert | |||||

| - | Established | 1860 | ||||

| - | Disestablished | 1862 | ||||

History

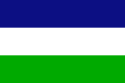

While visiting the region in 1860, Orélie-Antoine came to sympathise with the Mapuche cause, and a group of loncos (Mapuche tribal leaders) in turn elected him to the position of King[citation needed] —possibly in the belief that their cause might be better served with a European acting on their behalf. Orélie-Antoine then set about establishing a government in his capital of Perquenco, created a blue, white and green flag, and had coins minted for the nation under the name of Nouvelle France.His efforts at securing international recognition for the Mapuche[citation needed] were thwarted by the Chilean and Argentinian governments, who captured, imprisoned and then deported him on several occasions. The supposed founding of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia led to the approval of the Occupation of Araucanía by Chilean forces. Chilean president José Joaquín Pérez authorized Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez, commander of the Chilean troops invading Araucanía to capture Orélie-Antoine. He did not receive further punishment because he was deemed to be insane by both Chilean and Argentine authorities and sent to a madhouse in Chile. King Orélie-Antoine I eventually died penniless in France in 1878 after years of fruitless struggle to regain his perceived legitimate authority over his conquered kingdom. Historians Simon Collier and William F. Sater describe the Kingdom of Araucanía as a "curious and semi-comic episode".[3]

The later history of the "kingdom" belongs rather to "the obsessions of bourgeois France than to the politics of South America."[4] A French champagne salesman, Gustave Laviarde, impressed by the story, decided to assume the vacant throne as Aquiles I.[5] He was appointed heir to the throne by Orélie-Antoine.[6]

The first Araucanian king's present-day successor, Prince Philippe, lived in France until his death in 2014. Philippe, aka Philippe Boiry, is said to have purchased the title.[7] He renounced his predecessor's claims to the Kingdom, but he has kept alive the memory of Orélie-Antoine, and lent continued support to the on-going struggle for Mapuche self-determination. He authorised the minting a series of commemorative coins in cupronickel, silver, gold, and palladium since 1988.[8] When he visited Argentina and Chile once, he was met with hostility by the local media and cold-shouldered by most of the Mapuche organisations.[9]

As of August 2014, Prince Philippe's successor remains contested.[10]

Pretenders to the throne

- King Orelie-Antoine I (1860–78)[11]

- King Achilles I (1878–1902)[11][12]

- King Antoine II (1902–3)[11][13]

- Queen Laura Teresa I (1903–16)[13]

- King Antoine III (1916–52)[13]

- Prince Philippe (1952–2014)[13]

- Jean-Michel Parasiliti di Para

Orélie-Antoine de Tounens

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Orélie-Antoine de Tounens | |

|---|---|

Orélie-Antoine I, King of Araucania and Patagonia

|

|

| Born | May 12, 1825 Chourgnac, France |

| Died | September 17, 1878 (aged 53) Tourtoirac, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Aurelio Antonio de Tounens Orelio Antonio |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for | Creating the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia |

Early life

Orélie-Antoine de Tounens was born May 12, 1825 in Chourgnac, Dordogne. He moved to Coquimbo in Chile in 1858 and spent two years in Valparaíso and Santiago, studying Spanish and forming social connections. Later he moved to Valdivia where he met two French merchants, Lachaise and Desfontaines. He explained his plans to them about founding a French colony in the Araucanía. 1860 he moved to Araucanía (historic region) among the Mapuche who, at the time, were de jure and de facto an independent nation.Creation of new state

Based on his experience as a lawyer, de Tounens claimed that the area did not belong to recently independent Chile or Argentina, so he wanted to create an independent state south of the Biobío River. On November 17, 1860 he signed a declaration of Araucanían independence in the farm of French settler F. Desfontaine, who became his "foreign minister", and at an assembly of the chieftains of the various tribes of the territory known as "Araucanía" was voted a constitutional monarch by the tribal leaders. He created a national hymn, a flag, wrote a constitution, appointed ministers of agriculture, education, and defense (among other offices), and had coins minted for his kingdom.Later, a tribal leader from Patagonia approached him with the desire to become part of the kingdom. Patagonia was therefore united to his kingdom as well. He sent copies of the constitution to Chilean newspapers and El Mercurio published a portion of it on December 29, 1860. De Tounens returned to Valparaíso to wait for the representatives of the Chilean government. They ignored him. He also attempted to involve the French government in his idea, but the French consul, after making some inquiries, came to the conclusion that de Tounens was insane.

De Tounens returned to Araucanía where many Mapuche tribes were again preparing to fight the incursions of the Chilean Army during the occupation of Araucanía. In 1862 de Tounens proceeded to visit other tribes as well. However, his servant, Juan Bautista Rosales, contacted Chilean authorities who had de Tounens arrested. They put him on trial and were going to send him into an asylum when the French consulate intervened and he was deported to France.

Later life

De Tounens remained defiant and published his memoirs in 1863. In 1869, he returned to Araucanía, via Buenos Aires. The Mapuche were surprised to see him because Chileans had told them that they had executed him. De Tounens proceeded to reorganize his realm and again attracted attention of the Chilean authorities. Colonel Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez promised a reward for his head but the Mapuche decided to defend their unusual ally.De Tounens ran out of money in 1871 and had to return to France, where he published a second set of his memoirs. He also founded an Araucanian newspaper La Corona de Acero ("The Steel Crown"). In 1872, he proclaimed that he was seeking a bride so that he might sire an heir; indeed, the next year, he wrote to tell his brother that he intended to marry a "mademoiselle de Percy", but there is no evidence that he ever did.

In 1874, de Tounens tried again to return to his kingdom, this time with some arms and ammunition he was able to gather with the feeble support of a few entrepreneurs in Europe. Because he was persona non grata in Chile, he traveled with a false passport. However, he was recognized as soon as he landed in Bahía Blanca (on the Argentine coast) in July, 1874, and was summarily deported to France.

De Tounens tried to return again in 1876. However, local settlers robbed him on his way to Patagonia and handed him over to Chilean authorities. He also fell ill and had to go through an operation to survive. His health did not allow him to continue his journey and he had to return to France.

Orélie-Antoine de Tounens died on September 17, 1878, in Tourtoirac, France.

Bibliography

- Braun-Menéndez, Armando: El Reino de Araucanía y Patagonia. Editorial Francisco de Aguirre. 5a edición. Buenos Airey y Santiago de Chile, 1967. Primera edición: Emecé, Colección Buen Aire, Buenos Aires, 1945.

- Magne, Leo: L´extraordinaire aventure d´Antoine de Tounens, roi d´Araucanie-Patagonie. Editions France-Amérique latine, Paris 1950.

- Philippe Prince d´Araucanie: Histoire du Royaume d´Araucanie (1860–1979), une Dynastie de Princes Français en Amérique Latine. S.E.A., Paris 1979.

- Silva, Victor Domingo: El Rey de Araucanía. Empresa Editorial Zig-Zag. Santiago de Chile, 1936.

| Preceded by New Creation |

King of Araucania and Patagonia 1860–1878 |

Succeeded by |

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar